Investing

Key trends shaping the future of trade and implications for Vietnam

Published

1 year agoon

Surajit Rakshit, country head of global trade solutions at HSBC Vietnam, analyzes key trends that will shape the future of global trade and their implications for Vietnam.

Surajit Rakshit, country head of global trade solutions, HSBC Vietnam. Photo courtesy of the bank.

Against a challenging backdrop of high inflation, economic slowdown, and geopolitical conflicts, trade is expected to grow gradually. Despite a 1.2% contraction in merchandise trade volume in 2023, the WTO predicts a modest rebound with a growth of 2.6% in 2024 and 3.3% in 2025, mirroring similar projections for global GDP.

The global trade landscape is undergoing significant transformation due to technological advancements, evolving customer needs and sustainability initiatives. As the world gears up for a period of change, new trends will emerge that will reshape trade for years to come.

Shift to regionalization

The Covid-19 pandemic altered the world in many ways, one of which was the reversal of globalization we’ve seen in decades. As globalization becomes less prevalent, regionalization will be driven further by geopolitical factors which could further fragment the world into West-East and North-South trade blocs. This new era of multilateralism will see the emergence of new trade blocs and corridors in Asia and North America.

Over the next few years, there will be an increase in friendshoring – where supply chain networks are focused on countries regarded as political and economic allies. Meanwhile, bilateral and multilateral trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) will strengthen inter-regional trade corridors.

These would play a crucial role in promoting regionalization by reducing trade barriers, harmonizing regulations, improving infrastructure and connectivity, fostering economic cooperation, strengthening institutional frameworks, and enhancing cultural and social ties within the region.

Fast-growing emerging markets that are pursuing non-aligned strategies will benefit from increased trade in the multipolar landscape. Emerging markets like Mexico, Vietnam and India are positioning themselves as alternative sources of production to China, in particular for manufacturing goods, and seeing companies shift supply chain segments to their markets.

In the Middle East, countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia are capitalizing on their status as a relatively neutral political arbiter and their central geographical position as well as a trade facilitator between East and West and the Global South.

Supply chain restructuring

As a consequence of regionalization, corporates are prioritizing resilience over cost savings and efficiencies in their supply chains. They will de-risk their logistics networks by moving production out of areas affected by conflict, protectionism, and climate change. This may result in longer shipping routes and elevated costs but favor reliability and security.

Meanwhile, potential escalation of trade tensions between the U.S. and China will lead to a gap in global trade. Many emerging markets have filled in the gap as alternative sources of production for goods. This can create benefits to global supply chains and trade in the long term, especially as bystander countries have boosted their exports to the U.S. and the rest of the world, while their exports to China have remained largely unaffected. Countries like Vietnam, Thailand, South Korea and Mexico have surfaced as major export beneficiaries in this shift to alternative centers to Chinese exports.

Widespread AI adoption

Artificial intelligence (AI) is set to overtake blockchain to be the most disruptive technology for businesses and revolutionize trade in the future. This will herald a paradigm shift in the operating environment, as businesses embrace the ability to optimize supply chains, enhance efficiency and reduce costs through predictive analytics, drive data-driven market insights to capture new business opportunities, and use AI-powered trade finance solutions to streamline transactions.

AI holds a transformative power which is capable of influencing what is traded, how, and at what cost. The dawn of AI heralds a new era of digitally driven trade, fuelled by advancements in blockchain, big data, and additive manufacturing across sectors. While the potential is vast, concerns remain in shaping appropriate regulations amidst diverging rules on data flows and harmonization.

Implications for Vietnam

Asian supply chains are undergoing major structural changes, a number of which favor the shift to ASEAN. As Asia’s supply chains evolve, this has led to the rise of new locations in the region’s supply chain landscape. Countries that had historically been central to Asia’s supply chains, namely China, South Korea and Japan, are being joined by new players.

Vietnam, for instance, has emerged as a significant manufacturing and export hub, especially in electronics. Attracted by the country’s competitive labour costs and relatively stable political environment, companies such as Samsung and Intel have made significant investments. Samsung alone accounted for approximately 20% of Vietnam’s total exports in 2023, making Vietnam a crucial node in the global electronics supply chain.

Over the next few years, it is unlikely that we will witness a reduction in trade, but rather a shift in where trade takes place. This reconfiguration of global supply chains, driven by a combination of economic and geopolitical factors, offers multinational corporates opportunities to reinforce and optimize their logistics networks. It also represents a significant potential for Vietnam.

The future of trade is exciting as new trends and patterns evolve. Companies are looking at adopting smarter trade which would drive global economic growth and social progress.

You may like

-

Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone boasts over 1,000 GW of wind power potential: report

-

Uncertainty weighing on real estate

-

Central Vietnam city seeks $1.84 bln for 15 projects in economic zone

-

Green engagement rides high in Vietnam

-

New standards being reached within green industrial parks

-

Vietnam PM asks Warburg Pincus to invest ‘further and faster’

Investing

Bac Giang International Logistics Centre launched

Published

11 months agoon

April 27, 2025Bac Giang International Logistics Centre was launched on April 22 with an investment of $168 million, and is expected to become a crucial link in the global supply chain.

|

| Bac Giang International Logistics Centre launch |

Being invested by CNCTech Group, Dolphin Sea Air Services Corporation and Thien An Investment JSC, the logistics centre is located on National Highway 1A, which boasts first-class warehouse supply to meet the growing demand in the northern Vietnamese market.

Its strategic position within the golden economic triangle of Hanoi – Haiphong – Quang Ninh provides convenient connectivity to industrial zones and key logistics centres via national highways No.1A and No.37.

The centre is designed to meet growing demand for logistics infrastructure from businesses in Bac Giang and neighbouring provinces, positioning the area as a new node in northern Vietnam’s logistics network.

The project is a strategic product as a key component of the logistics spearhead in CNCTech Group’s industrial and logistics infrastructure ecosystem. It has been approved by the prime minister as a national level-II logistics centre, covering a planned area of 67 hectares.

At the launch ceremony, Chairman of Bac Giang People’s Committee Nguyen Viet Oanh said, “In recent years, the province’s socioeconomic development has made remarkable strides. Transportation, urban, industrial, and social infrastructure have been synchronously invested in and have yielded high efficiency. However, the province’s logistics service sector has not yet matched its potential, advantages, and socioeconomic development level. The logistics system remains fragmented, transportation costs are high, and trade delivery times are prolonged.”

Recognising this bottleneck, the local authorities have focused on directing the robust development of the logistics system, incorporating it into the provincial plan. This includes developing eight comprehensive logistics centres covering nearly 500ha, three inland container depots, and 33 inland waterway ports.

“Bac Giang, with its strategic location between Hanoi and border provinces, has long been known as a dynamic industrial hub. The remarkable development of the province’s industrial parks has created a solid foundation for the establishment of Bac Giang International Logistics Centre. This centre is not only located on vital transportation routes such as Hanoi-Lang Son Expressway but also directly connects to major border gates, optimising the transport of goods from Bac Giang to the world,” said Oanh.

|

| A model of the logistics centre |

The project is not merely a warehousing facility, but also a symbol of the integration of modern infrastructure and advanced technology. The centre includes multifunctional warehouse areas, customs-controlled warehouses, non-tariff warehouses, and automated warehouses, meeting the needs of various industries. Notably, it integrates end-to-end logistics solutions, supporting businesses in optimising transportation costs and enhancing production efficiency.

With a long-term vision, the centre aims not only to optimise domestic supply chains but also to become a key connection point in the global logistics network.

Nguyen Van Hung, chairman of the Board of Members of CNC Tech Group, shared, “The establishment of this centre is a strategic step in developing Vietnam’s logistics infrastructure. We are committed to long-term and robust investment in this sector, as logistics is not just infrastructure but an indispensable part of enhancing the competitiveness of Vietnamese businesses on the international stage.”

Vietnam has taken strong action to promote green development among businesses, amid the country facing challenges in finance and technology.

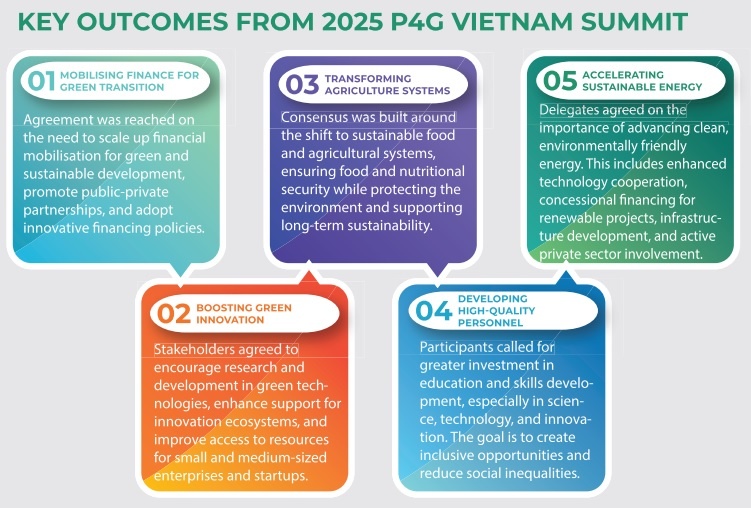

Vietnamese Party General Secretary To Lam told the fourth Summit of the Partnering for Green Growth and the Global Goals 2030 (P4G), organised last week in Hanoi, that Vietnam is focused on strategic breakthroughs to prepare for a national development process that is fast, inclusive, and sustainable.

|

| The summit in Hanoi covered areas from finance and banking to agriculture and technology Photo: Dung Minh |

“We will strongly transform political commitments into practical actions, creating motivation for businesses and the whole society to participate in sustainable economic development, in which green institutions are the decisive foundation,” General Secretary Lam stressed at a hall attended by government leaders, UN representatives, diplomats, experts, and entrepreneurs.

General Secretary Lam also stressed that when it comes to green transformation, despite being a developing country with a transitional economy and limited resources, Vietnam has achieved some important results.

Besides making a 2050 net-zero commitment in 2021, Vietnam also endorsed six global initiatives at the time, on forest and land use, methane, clean power transition, sustainable food and agriculture, and more.

“Vietnam is now a leading country in supplying renewable energy in ASEAN, with wind and solar power capacity accounting for two-thirds of ASEAN’s total capacity,” he said.

“Additionally, Vietnam is also a good example of encouraging sustainable agriculture. The initiative to develop one million hectares of high-quality and low-emission specialised rice is a pioneering model that many partners and international organisations are interested in.”

A greener future

Vietnam is an active and responsible member of all multilateral mechanisms and major initiatives on green growth and energy transition such as the Paris Agreement on climate change, the Just Energy Transition Partnership, and the P4G.

“However, as a developing country with a transitional economy, we also face many challenges in terms of financial resources, technology, personnel, and resilience to the impacts of climate change and geopolitical fluctuations globally,” said General Secretary Lam.

The summit adopted the Hanoi Declaration, strongly affirming commitments to sustainable growth with people at the centre, and a determination to collaborate responsibly in addressing current global challenges. Vietnam is expected to enjoy continued support from the international community in its journey to a green economy including energy transition.

According to the World Bank, to ensure sufficient funding for responding to climate change, mobilising domestic finance is possible, but external support is needed.

Overall, Vietnam’s total incremental financing needs for the resilient and decarbonising pathways could reach $368 billion over 2022–2040, or approximately 6.8 per cent of GDP per year.

The resilient pathway alone will account for about two-thirds of this amount, as substantial financing will be required to protect the country’s assets and infrastructure as well as vulnerable people.

The cost of the decarbonising pathway will mainly arise from the energy sector – investments in renewables and managing the transition away from coal might cost around $64 billion between 2022 and 2040. All the figures are in net present value terms at a discount rate of 6 per cent.

This $368 billion in financing needs will include $184 billion from private investments or about 3.4 per cent of GDP annually, $130 billion or about 2.4 per cent of GDP annually from the state budget; and $54 billion or about 1 per cent of GDP per year from external sources.

Choi Youngsam, South Korean Ambassador to Vietnam, said that within the P4G framework, South Korea and Vietnam have completed or are currently implementing joint projects in areas such as food and agriculture, energy, water, and urban development.

“Looking ahead, both sides are expected to broaden and deepen their partnership under the P4G framework,” he said.

At the P4G Summit held in Seoul in May 2021, the two governments signed the Framework Agreement on Cooperation in Response to Climate Change, laying a solid policy foundation for the implementation of international emissions reduction ventures.

“On this basis, I hope that South Korea will leverage its technological expertise and financial resources to carry out greenhouse gas emission reduction projects in Vietnam, with both countries mutually recognising the results,” Ambassador Youngsam said.

“This would contribute to establishing a win-win model of emissions reduction cooperation. At the same time, I look forward to seeing active engagement from South Korean enterprises possessing green technologies, in close collaboration with the Vietnamese government.”

Encouraging developments

Deputy Minister of Science and Technology Hoang Minh said at a policy dialogue on the sidelines of the P4G 2025 that the active participation and strong cooperation from stakeholders – from the public and private sectors to international organisations – can help materialise Vietnam’s aspiration of an efficient and sustainable innovative startup ecosystem.

“Innovation, creative entrepreneurship and collaboration are key to solving environmental problems, while encouraging the development of a circular economy,” he said.

Vietnam currently has over 4,000 innovative startups, including two unicorns valued at over $1 billion, 11 companies valued at over $100 million, more than 1,400 startup support organisations, 202 co-working spaces, 208 investment funds, and 35 business promotion organisations. Among these, it is estimated that around 200–300 companies focus on green transition, covering areas such as renewable energy, environmental technology, sustainable agriculture, and the circular economy.

According to the Vietnamese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, hosting the fourth P4G Conference is of great significance to Vietnam. It is aimed to boost its role as a good friend, a reliable partner, and a responsible member of P4G and the international community. Moreover, it is also aimed to reaffirm its commitment to sustainable development, energy transition, and the goal of carbon neutrality by 2050. Besides that, it is aimed at contributing to raising awareness of international cooperation and encouraging the role and voice of developing countries in the sector of green growth and sustainable development.

| Pham Minh Chinh, Prime Minister

For Vietnam, together with digital transformation, we identify green transition as an objective necessity, a key factor, and a breakthrough driving force to promote rapid growth and sustainable development. This aligns with the strategic goal of becoming a developing country with modern industry and upper-middle income by 2030, and a developed, high-income country by 2045, while also contributing to the gradual realisation of Vietnam’s commitment at COP26 to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. From practical experience with initial positive results, especially in renewable energy, green agricultural development, and participation in multilateral mechanisms and initiatives on green transformation, as the host of the fourth P4G Summit, Vietnam has three suggestions for discussions which pave the way for further cooperation in the coming time. First is to perfect green mindset, with a focus placed on the development of science and technology, innovation, and digital transformation linked to green growth. This includes recognising that green resources stem from green thinking, green growth is driven by green transition, and green resources arises from the green awareness of people and businesses in nations and regions throughout the world. Second is to build a responsible green community, in which, the government plays a guiding role, encouraging, and ensuring a stable and favourable institutional environment for green growth. The private sector functions as a core investor into technological development and the dissemination of green standards. The scientific community take the lead in developing green technologies and training green human resources. Meanwhile, citizens continuously enhance their green awareness, truly becoming beneficiaries of the outcomes of green transformation. Thirdly, it is necessary to promote international cooperation and robust multilateral green cooperation models, particularly public-private partnerships, South-South cooperation, North-South cooperation, and multilateral cooperation frameworks. This is aimed at removing institutional barriers, enhancing access, and speeding up the flow of green capital, green technology, and green governance. Developed countries should take the lead in fulfilling commitments to provide financial, technological, and institutional reform support. Meanwhile, developing countries would need to leverage their internal strengths and effectively utilise external resources. |

Investing

Public-private partnerships a lever for greener innovation

Published

11 months agoon

April 26, 2025Public-private partnerships are no longer a supporting mechanism, but a strategic pillar in the global pursuit of the green transition.

The high-level dialogue between government leaders and businesses at the 2025 P4G Vietnam Summit last week, chaired by Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, brought together senior officials, global experts, international organisations, and private sector leaders.

They recognised that the climate crisis, digital transformation, and resource depletion are converging in ways that demand not only innovation, but deep and long-term collaboration between the public and private sectors.

UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed acknowledged Vietnam’s leadership in renewable energy, noting its potential to attract trillions in sustainable investment.

“Emerging economies must accelerate the adoption of new investment models, particularly those that align private capital with green infrastructure priorities. Governments must work with the private sector to expand ambition, strengthen accountability, and deliver real impact,” she said.

From Italy, Prime Minister’s Climate Envoy Francesco Corvaro stressed that public-private partnerships (PPPs) are indispensable in addressing climate finance gaps. Drawing from Italy’s experience, he underscored the importance of public investment as a risk mitigator, enabling private sector participation in clean energy and smart infrastructure projects.

“Public investment can unlock private capital, but local authorities must lead with clear priorities and long-term vision,” Corvaro noted. “You can’t talk about renewables, AI, or digital infrastructure without modern, resilient grids, and that requires strong public-private alignment.” he said

Alejandro Dorado, Spain’s High Commissioner for Circular Economy, argued that the case for stronger PPPs lies at the intersection of two accelerating forces: the environmental-climate crisis and a wave of disruptive technologies.

“In a world where AI, green technologies, and digitalisation are reshaping the global economy, the clock is ticking. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, we have less than a decade to prevent irreversible climate disaster. Meanwhile, the World Economic Forum has identified biodiversity loss as one of the most severe economic risks,” he said.

|

Dorado added that while multilateralism is being questioned or weakened in some quarters, the need for cooperation has never been more urgent – both to solve environmental challenges and to harness the transformative potential of innovation.

“No government or business can tackle these crises alone. Public authorities must provide the regulatory frameworks, fiscal incentives, and infrastructure deployment needed at scale to safeguard the common good,” he stressed.

From the business side, Stuart Livesey, country representative of Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP), provided a frank but optimistic outlook. Livesey stated CIP’s commitment to supporting Vietnam’s transition, but emphasised the need for enabling conditions.

“What we seek are clear, bankable projects underpinned by stable regulatory frameworks, collaborating with strong local partnerships. This is where public-private cooperation becomes not just helpful, but essential,” Livesey noted. “Over the next 10-15 years, the offshore wind sector and green energy consumers will trigger massive demand for new technologies, digital solutions, and skilled labour.”

To meet this demand, CIP is investing not only in infrastructure, but also in capacity building, research and development, and local supply chain development through partnerships with Vietnamese universities.

Still, he acknowledged barriers. “Technological application and innovation in green projects face challenges, from long-term financing constraints and skilled labour shortages to fragmented policy signals. These are not unique to Vietnam, but they require proactive, tailored local solutions,” he said. “Addressing issues such as grid availability, regulatory clarity, and inter-ministerial coordination will be critical.”

Tim Evans, CEO of HSBC Vietnam, stated that the banking sector is ready to facilitate green finance, particularly in sectors aligned with national climate targets.

“We see ourselves as a bridge between global capital and local sustainability goals. The clearer the pipeline of bankable, climate-aligned projects, the faster we can move capital,” he noted. “What’s crucial now is consistency in policy and coordination among stakeholders to ensure these projects reach maturity.”

Bac Giang International Logistics Centre launched

Vietnam’s Exclusive Economic Zone boasts over 1,000 GW of wind power potential: report

Uncertainty weighing on real estate

Central Vietnam city seeks $1.84 bln for 15 projects in economic zone